I made a 10 day trip to Beijing in late October/early November 2025. This was my first trip to Beijing (and China) since October 2019. I visited Beijing eight times between 2016 and 2019, for at least a week on each occasion. I have visited many other Chinese cities as well, including a number of visits to Shanghai, but of the many Chinese cities I have visited I most like Beijing.

I will describe in this post a number of the places I visited during my trip, illustrated with photos.

I stayed at the Prime Hotel (above) in Wangfujing Street as I have done on previous visits. It is at the corner of Wangfujing Street and Dongsi West Street, a short distance from the National Art Museum of China and 15 minutes’ walk from the northwestern corner of the Forbidden City. The Prime Hotel, known in Chinese as 华侨大厦 (Overseas Chinese Hotel), was built during the 1990s to replace a previous hotel at the same location that was completed in 1959. The original hotel had been one of ‘Ten Great Buildings’ (十大建筑) that were constructed in 1959 to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the founding of the PRC. The other buildings included the Great Hall of the People, the National Museum of China and the Workers’ Stadium.

The Prime Hotel underwent a major refurbishment during the pandemic years and was more comfortable than when I stayed there in the past, but still very inexpensive compared with comparable hotels in London. Outwardly it was little changed, but the junction at which it is located was much neater in appearance, with newly laid pavements and long rows of rental bikes in front, plus entrances to a new subway station (the National Art Museum station on subway LIne 8) on three corners of the junction.

Street. On my last visit in 2019 there were many construction hoardings at this junction, plus jumbles of rental bikes strewn across the pavements. The hoardings have now been replaced by entrances to the new National Art Museum subway station on Line 8 of the Beijing subway. The rental bikes are all now neatly arranged, as we also see in London now. The junction had a much neater and cleaner appearance than I remember from previous visits.

There is a traditional Beijing residential area behind the Prime Hotel, a collection of one and two storey houses with very small courtyards. It appeared unchanged from what I saw on previous visits, apart from the many air conditioning units at roof level. Residential and office buildings further away from the hotel now have solar panels on their roofs, which I did not see in the past.

I visited again the National Art Museum of China, just across the junction from the Prime Hotel, as I have done on all previous visits to Beijing. I took this particular photo in March 2016, but the external appearance of the Art Museum has not substantially changed since then. It was originally built between 1958 and 1962, and opened to visitors in 1963. It is well worth visiting this Museum on every trip to Beijing, as there are exhibitions spread out over several floors and they are frequently changed.

The exhibition I liked the most on this visit was a selection of ‘Modern Day Classics’ from the Museum’s permanent collection. The English title of the exhibition was ‘Honoring the Spirit: Homage to the Classics’. It included pieces by two artists whose work I had not seen before:

This is a painting by Chen Dayu (陈大羽) entitled 雨浥红蕖冉冉香 (literally ‘rain soaked softly drooping fragrant red lotus’), painted in 1963. Chen Dayu (1912 – 2001) was a Chinese painter, calligrapher, seal carver and educator. He graduated from Shanghai Art College in 1935 and became an apprentice of the very famous Chinese artist Qi Baishi who died in 1957. He is best known for his paintings of roosters.

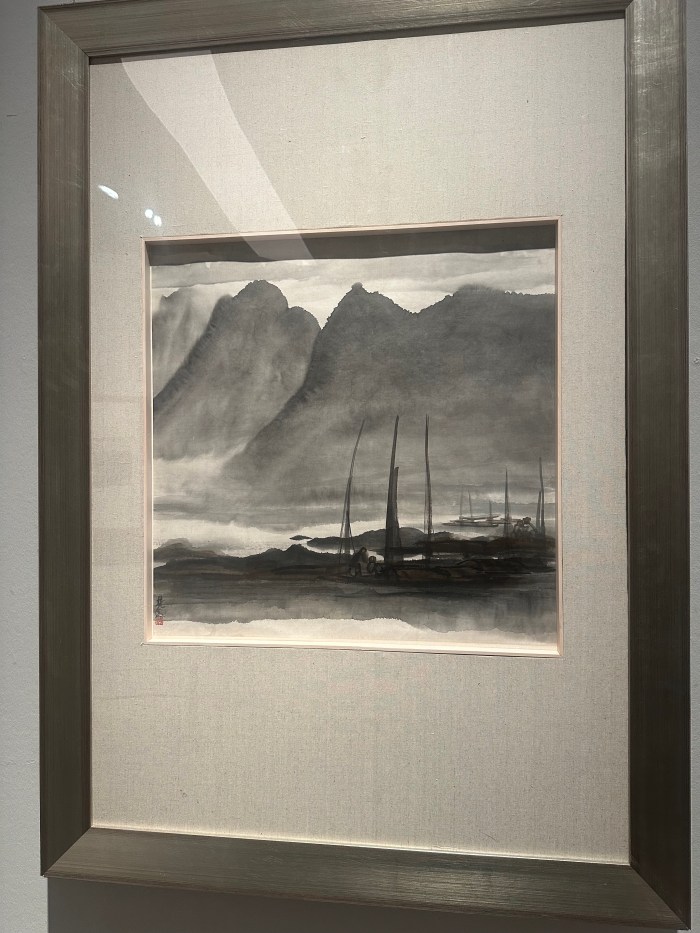

This is a painting by Lin Fengmian (林风眠) entitled ‘风景’ (literally ‘Landscape’) painted in 1961. Lin Fengmian (1900 – 1991) was a Chinese painter who studied in Europe and blended Chinese and Western styles in his work. He was a student at the Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris during the 1920s and also travelled in Germany. After returning to China he founded the Hangzhou National College of Art and taught western painting along with other artists who had trained in France. He was persecuted and imprisoned for four years during the Cultural Revolution, when many of his works were destroyed. He spent his last years in Hong Kong.

I visited the Peking University Red Building again this time, as I have done on all of my previous visits to Beijing. This building is around 10 minutes’ walk from the Prime Hotel and was the original location of Peking University, which later moved to its present location in northwest Beijing. The Red Building was the centre of a major demonstration by students in May 1919 that was sparked off by the decision of the Versailles Peace Conference to award control over Shandong Province (previously controlled by Germany) to Japan. Professors and library staff at the Red Building in 1919 included Cai Yuanpei (the President of the University), Lu Xun (a Professor and the most famous Chinese author of the 20th century), Li Dazhao (head of the library), Chin Duxiu (a Professor) and Mao Zedong (a library assistant). The latter three went on to found the Communist Party of China two years later, but Cai Yuanpei, Lu Xun and other staff at the University were more drawn to ideas of constitutional democracy.

I first became aware of the Peking University Red Building before I travelled to China, as a result of reading Rana Mitter’s book ‘A Bitter Revolution’ (published in 2004). He describes the Red Building and its history in considerable detail and quotes (at page 48 of the book) from a memoir by Zhu Haitao who wrote that: “The nicest thing about [being at Peking University] was searching for teachers. The doors of the university were open to anybody who wanted to come in…”. It was largely as a result of reading Rana Mitter’s book that I decided to begin studying Chinese in early 2015, initially by attending Saturday morning classes at SOAS in London. When I made my first visit to Beijing a year later, the Red Building was one of the first places I wanted to visit. I first went there on 23rd March 2016, but I initially hesitated at the entrance as there was no obvious ‘entry’ gate and I wondered if it was indeed open to the public. After some time a security person emerged from a small gatehouse and urged me to go in, assuring me it was open to the public, though neither of us could properly understand each other. In any case I felt welcomed to the building and toured the original classrooms, offices and library rooms on the ground floor. I also viewed the exhibition that was then on display inside and the separate display of photographs and captions in glass cabinets along the outer wall of the building fronting on the road outside. There were few other visitors and it was all very quiet. The atmosphere was, however, consistent with Zhu Haitao’s description of the doors of the university being ‘open to anybody who wanted to come in’. I visited the Red Building again on each of my subsequent visits to Beijing between 2016 and 2019, seeing a different exhibition each time, but the ambience remained the same – quiet, with relatively few visitors.

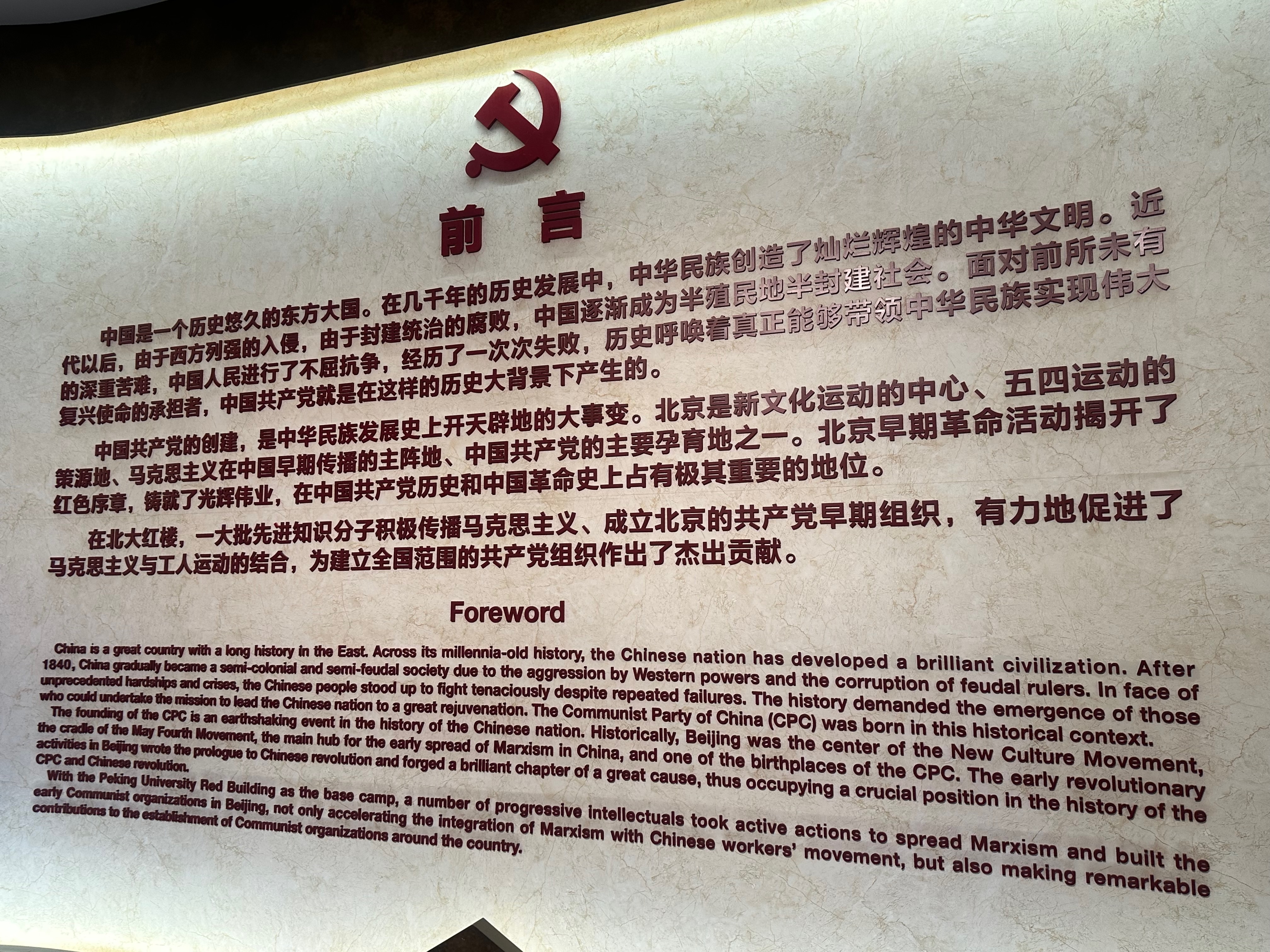

I found the Red Building rather different on my latest visit, however. On my visits between 2016 and 2019, there was more or less equal emphasis in the exhibitions on the ‘democrats’ like Cai Yuanpei, and the ‘communists’ who went on to found the Party. I also read a report during that period that the Chinese leadership were unsure how to deal with the Red Building, as it was by no means solely linked with the later founding of the Party. By contrast, I found that the current exhibition was much more focussed on linking the 1919 protests with the founding of the Party. There were also far more visitors at the Red Building on this occasion, almost all Chinese as on previous occasions, but clearly demonstrating a much higher level of interest among the Chinese public in the Red Building than in the past.

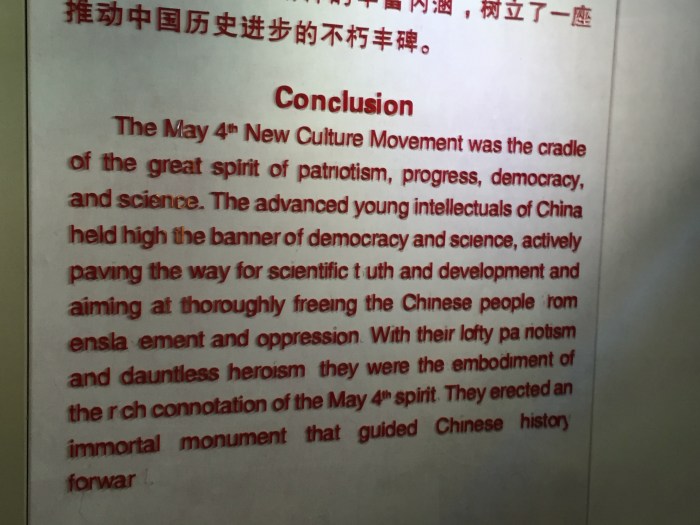

The above panel was one I saw at the Red Building in March 2016, almost 10 years ago. This panel states: “The May 4th New Culture Movement was the cradle of the great spirit of patriotism, progress, democracy and science. The advanced young intellectuals of China held high the banner of democracy and science, actively paving the way for scientific truth and development and aiming at thoroughly freeing the Chinese people from enslavement and oppression”. That is a rather different emphasis from what I saw in the introductory panel to the current exhibition in November 2025.

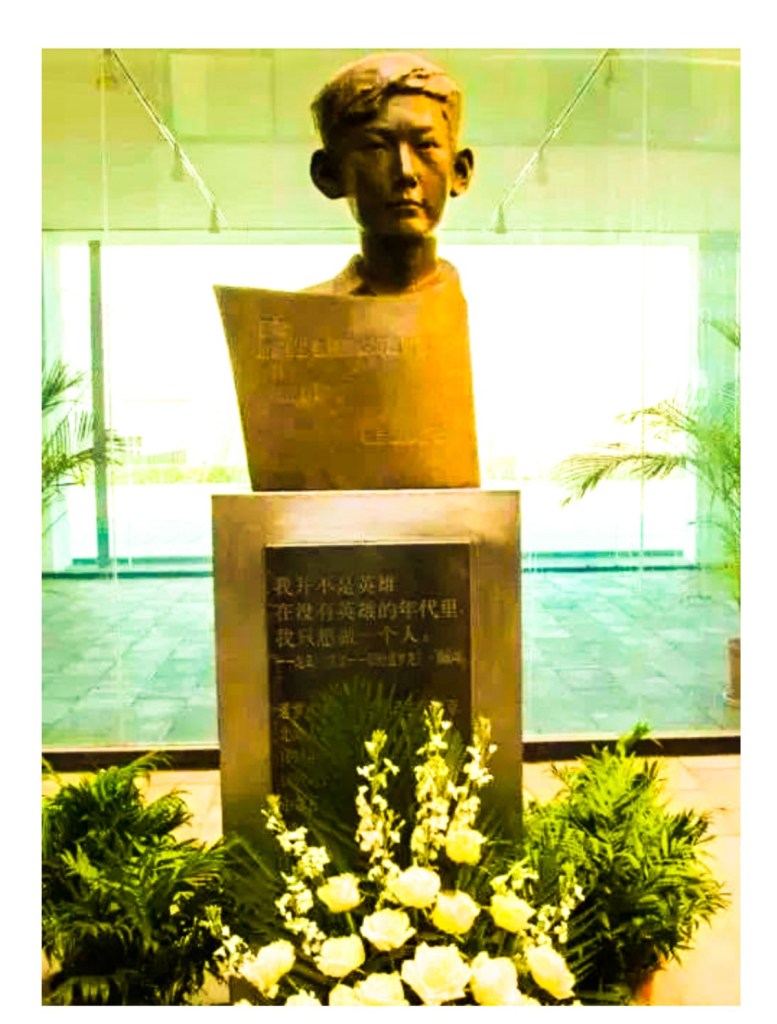

I read before my visit that there was a sculpture of Yu Luoke at this particular Art Museum and went there by taxi one afternoon from my hotel. When I arrived, however, the young staff members I spoke with knew nothing about it, or even about Yu Luoke for that matter. They even called up the manager of the Museum, who was in a different building, but the manager also had no knowledge of it. It appears the sculpture must have been part of a short-term exhibition, or that it was removed at a later time. The staff asked me to have a look at their current modern art exhibition, but it looked very grim to me and I said that I was more interested in reading about Chinese historical figures than in modern art. One of the staff members then looked up Yu Luoke on his phone and said he would read more about his tragic story.

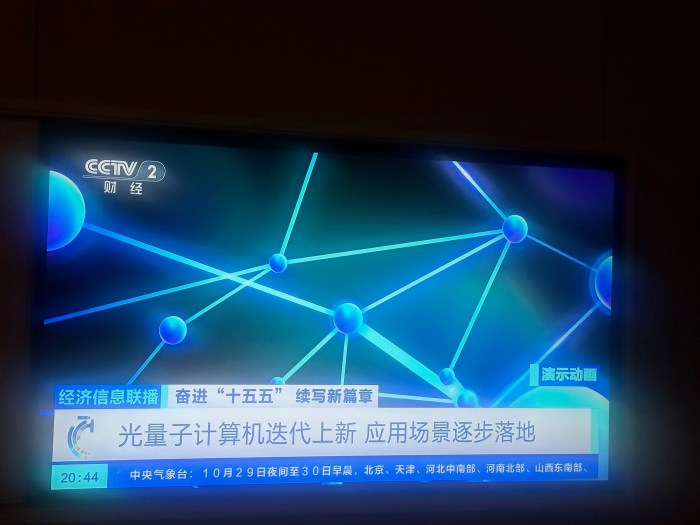

One evening during my visit, I happened to watch a short report on recent scientific developments on the Chinese CCTV2 channel ‘Finance and Economics’. In the course of just five or ten minutes it discussed developments in ‘green hydrogen energy’, ‘light quantum computing’, the promotion of research into the ‘practical application’ of the results of science and technology research, the space mission due to be launched the next day, and a push to expand production of health and cosmetic products. I did not understand all of this at the time, but took photos of the TV screen and translated the captions later. That report was followed by advertisements for the latest Honor smartphone, BYD electric cars and Huawei’s new phone operating system. On the same evening the CCTV news channel devoted considerable time to reporting on the meeting in Busan, South Korea between Xi Jinping and Donald Trump, including footage of the actual meeting. That was clearly regarded as a very important event in China.

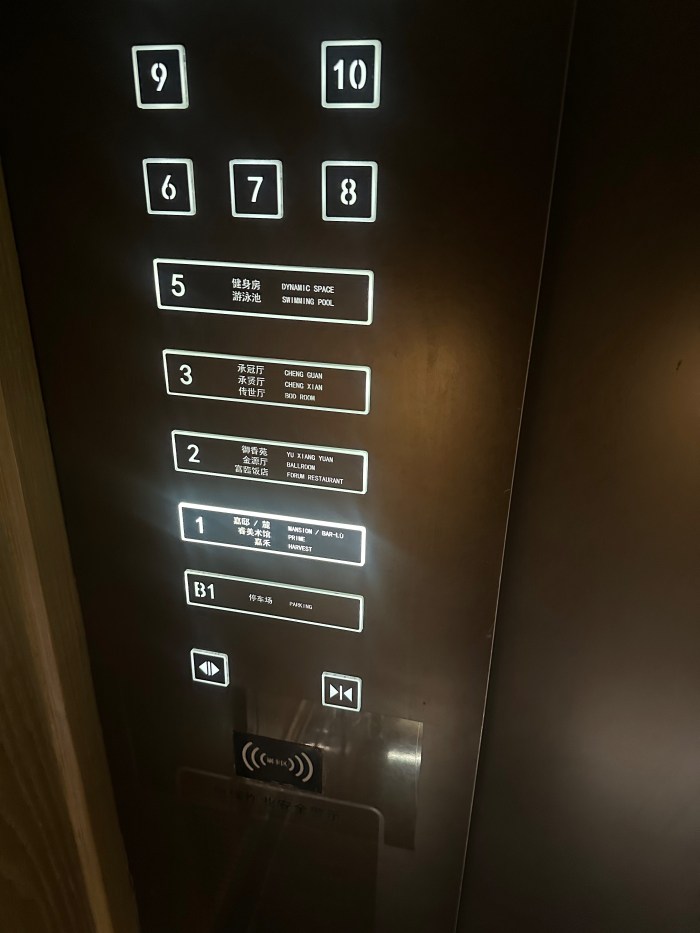

This is the floor selection panel in one of the lifts at the Prime Hotel. You will note that there is no floor 4. That is because the number 4 is considered to be inauspicious in China, as its sound is similar to the sound of the character for ‘death’ (though not the same tone).

My return trip from Beijing to London went smoothly, starting with a taxi to the airport that was organised by the concierge at the hotel. My next trip to China will be to Shanghai.

Michael Ingle (michaelingle01@gmail.com)

Categories: Uncategorized

Leave a comment